Pro-Palestinian Messaging in Children's Media During the Lebanese Civil War

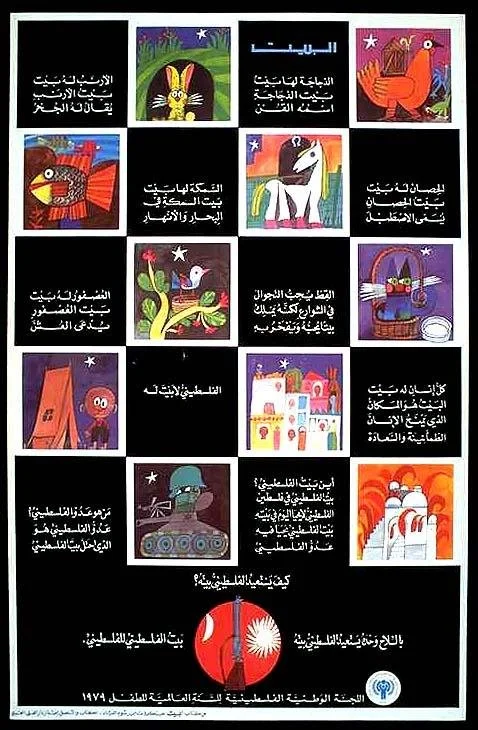

Figure 1. Al-Bayt (Home) poster produced by Dar al-Fata al-Arabi for the International Year of the Child (1979), adapted from the book of the same title, written by Zakariyya Tamir and illustrated by Mohieddin Ellabad.

Political posters are understood as key agents in the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), yet archetypical representations neglect the diversity of Lebanese visual culture and the media that subverts popular notions of ‘propaganda.’ To this end, the phenomenon of pro-Palestinian messaging in children’s media of the 1970s and 1980s merits special focus, and in particular, the work of Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, a Beirut-based children's publishing house affiliated with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). By 1974, when Dar al-Fata was established, the PLO was headquartered in Lebanon, which had experienced a mass influx of Palestinian refugees following the Arab-Israeli War (1948-49). Within a year of the house’s founding, however, Lebanon became embroiled in a complex and protracted civil war, which saw an Israeli invasion of the country in 1982, forcing Dar al-Fata’s relocation to Egypt. Pan-Arabist and pro-Palestinian convictions were closely linked during the conflict and while Dar al-Fata sought to elevate revolutionary politics in the global south more generally, its pro-Palestinian media is the only instance of any contemporary Arab publisher directly addressing a nation of children. By analyzing three primary source examples — Al-Bayt [Home] (1974, 1979) and The Palestinian Alphabet (1985) by Mohieddin Ellabbad, and Jerusalem is in the Heart by Helmi el-Touni — this essay will address the motivations for the creation of such posters, their relation to contemporary artistic and ideological movements, and how their use of topical motifs aimed to instill a sense of identity, rootedness, and resistance in their young Palestinian audience.

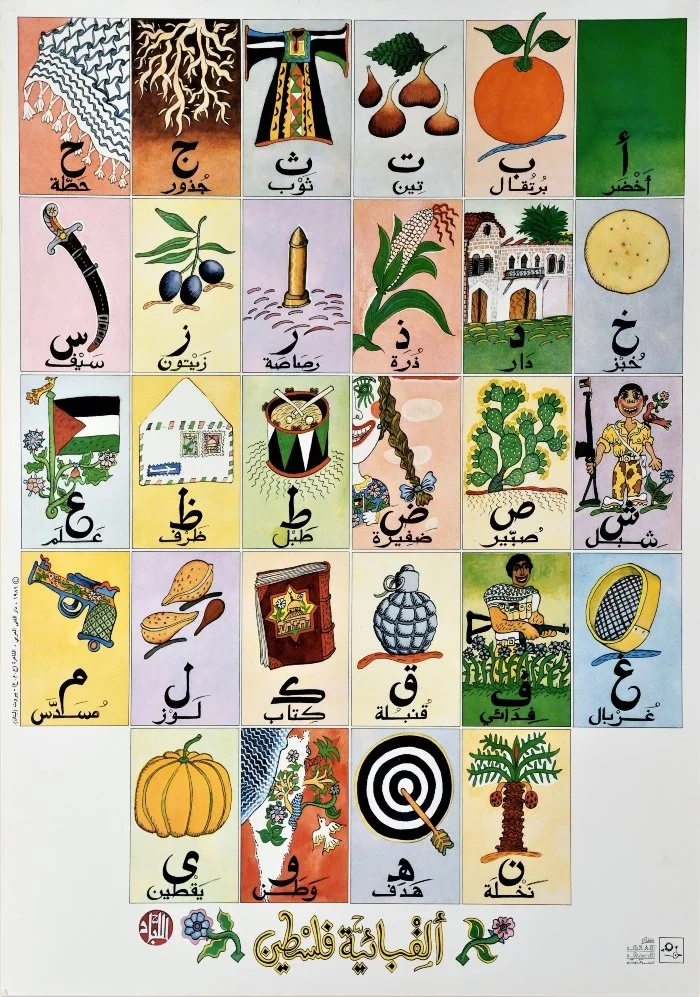

Figure 2. The Palestinian Alphabet (1985) poster, produced by Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, adapted from the 1975 book, illustrated by Mohieddin Ellabbad.

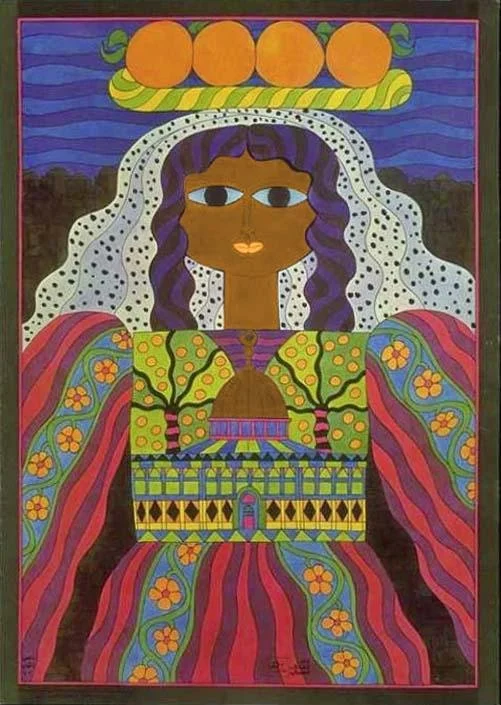

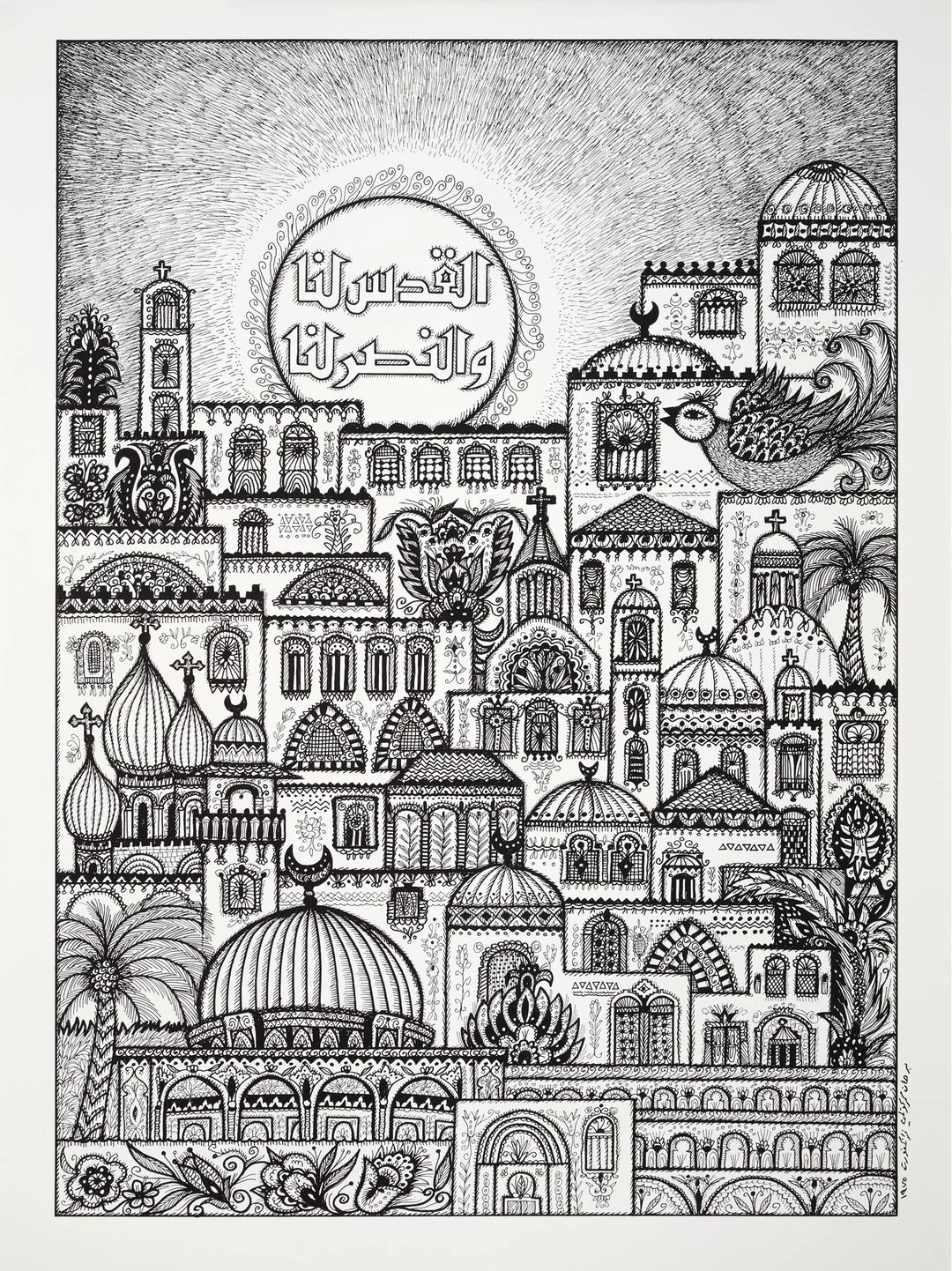

Figure 3. Jerusalem is in the Heart (1977) poster produced by Dar al-Fata al-Arabi and designed by Helmi el-Touni.

All three posters contain the themes, ethos, and purpose of the Dar al-Fata publishing house. The subject of Palestine dominates these works. Al-Bayt (fig. 1) utilizes familiar pedagogical storytelling to explore the displacement of Palestinian children. Adapted from Ellabad’s 1974 book, each frame of the poster explains that ‘‘The chicken has a home. The home of the chicken is called the coop. / The rabbit has a home. The home of the rabbit is called the burrow’’ and so on. It concludes: ‘‘Everyone needs a home. All humans need a home that is secure and peaceful. Today, the Palestinians do not have a home.’’ In figure 2, the Arabic alphabet is taught through symbols of Palestinian resistance, heritage, and culture. An English translation might read for instance: B is for bullet ( رصاصة), F is for freedom fighter (فدائي), O is for orange (فدائي) and S is for sword (سيف). Lastly, Jerusalem is in the Heart (fig. 3) emphasizes the Dome of the Rock as a lasting connection to the Palestinian homeland. The motifs of displacement, resistance, and rootedness demonstrate Dar al-Fata’s status as the PLO’s ‘‘cultural program.’’ Twenty-five percent of publications at the house were dedicated to the Palestinian cause, seeking ‘‘to instill in children the learning required for the battle of liberating the Palestinian homeland.” The publishers envisioned it as pan-Arab in scope, although neither of the illustrators, Ellabbad nor el-Touni, had personal connections to Palestine. Dar al-Fata employed artists from all over the Arab world, stimulating the collaboration of authors like the Syrian, Zakariyya Tamir, and the Egyptian illustrator, Ellabbad. Arab unity was not only represented but promoted through the publisher’s international approach. Translated copies of Al-Bayt were in fact presented to delegates at the UN General Assembly during PLO chairman, Yasser Arafat’s 1974 speech. The purpose of the documents can, therefore, be linked back to the PLO’s core aspiration: the international revolutionary struggle for a liberated Palestine.

Despite its regional focus, Dar al-Fata was fundamentally outward-looking. It’s proponents came from the Egyptian school and were attracted to Lebanon during its rise as the literary entrepôt of the Arab world ㅡ what contemporaries titled the “Arab-Hanoi.’’ Ellabbad and al-Touni, for example, left Cairo for Beirut in the early 1970s. They saw the new government in Egypt under Anwar al-Sadat as incompatible with the literary ethos of iltizām (committed literature, also referred to as literature engagée) which aimed to decolonize the Arabic page. For El-Touni, iltizām involved a reappropriation of the stylistic language of medieval Arabic miniatures. With their flowing lines, gold embellishment and stark color contrast, his posters evoke a historic Middle Eastern style in a politically modern, and beautiful way. Ellabbad’s relaxed style likewise rejects an Americanized, Disney-esque mode of illustration, which he interpreted as symptomatic of bourgeois consumerism. Such approaches parallel other dissident artists, who contributed to the symbiotic success of Beiruti publishing during the era — ‘‘Egypt writes, Lebanon prints, and Iraq reads.’’ Al-Bayt, The Palestinian Alphabet, and Jerusalem is in the Heart represent the pinnacle of this exchange, articulating the new forms Palestinian art took ‘‘to reach the Arab man’’ and child.

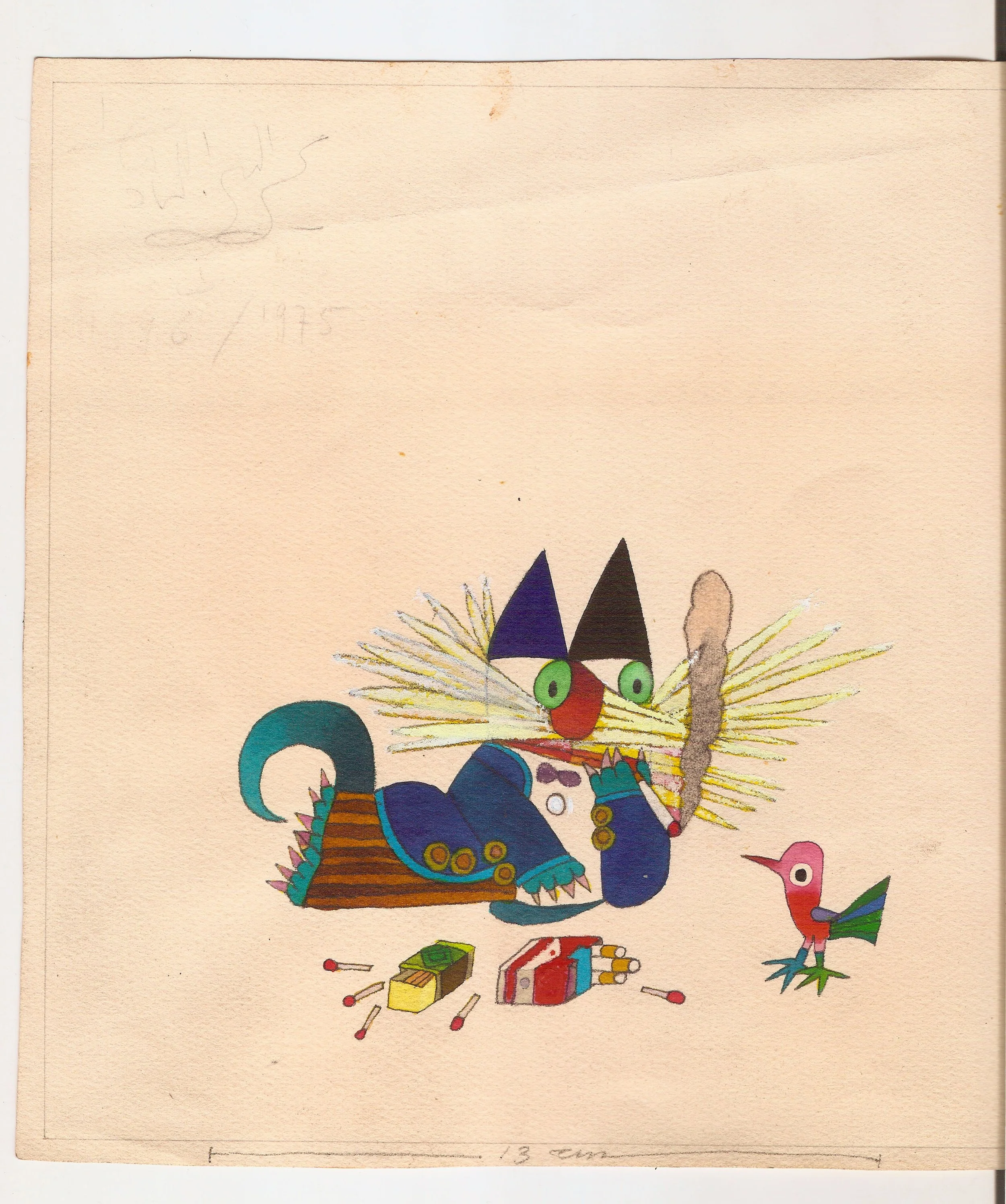

Figure 4. Preliminary cover illustration for the 1975 book, The Cat’s Banquet, produced by Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, written by Zakariyya Tamir, and illustrated by Mohieddin Ellabbad.

Each poster represents the revolutionary, anti-imperialist, and nationalist currents of the long sixties. The guns, featured in Al-Bayt and The Palestinian Alphabet, draw upon the imagery of radical, guerilla movements. By highlighting the role of the fida’i (Palestinian freedom fighters) and making no reference to ‘state,’ Ellabbad reinforces this theme. The AK-47 in particular symbolized unconventional revolutionary warfare and a re-orientation of liberation movements towards non-state actors; the fida’i, too, was solidified as a quintessential trope of pro-Palestinian media by PLO propagandist, Ismail Shammout. Echoes of anti-imperialist themes appear in the feline figure of The Cats Banquet (1975) — a recurring character in the Dar al-Fata series. This Marlboro-smoking, Coca-Cola-drinking capitalist (fig. 4) represented the corrupting influence of cultural imperialism. The inequality between the bourgeois cat and the dispossessed Palestinian reveals an element of anti-American messaging aligning thematically with the 7.28% of Dar al-Fata books that feature foreign domination. Yet, imperialism was not addressed through militaristic imagery and ideological satire alone.

Figure 5. Jerusalem is Ours, Victory is Ours (1975) produced by Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, illustrated by Burhan Karkutli, based on the 1967 song, ‘’Zahrat Al Mada’in,’’ by Lebanese singer, Fairuz.

The Palestinian Alphabet and Jerusalem is in the Heart portray Palestinian heritage as both a source of national beauty and political resistance. Deep-rooted trees, blooming flowers, and creeping vines counter Zionist portrayals of Palestine as ‘‘an empty desert,’’ which was only brought to life by Israeli settlement. The Dome of the Rock represents the occupation from which Jerusalem must be liberated, mirroring the work of Burhan Karkutli (fig. 5). These works are consistent with the wider catalog of revolutionary PLO propaganda.

Figure 6. A miniature from a 1465 of Nahj al-Faradis (1465) by Al-Sarai.

Figure 7. A miniature from a 16th century manuscript of Shanama by Fidarwasi.

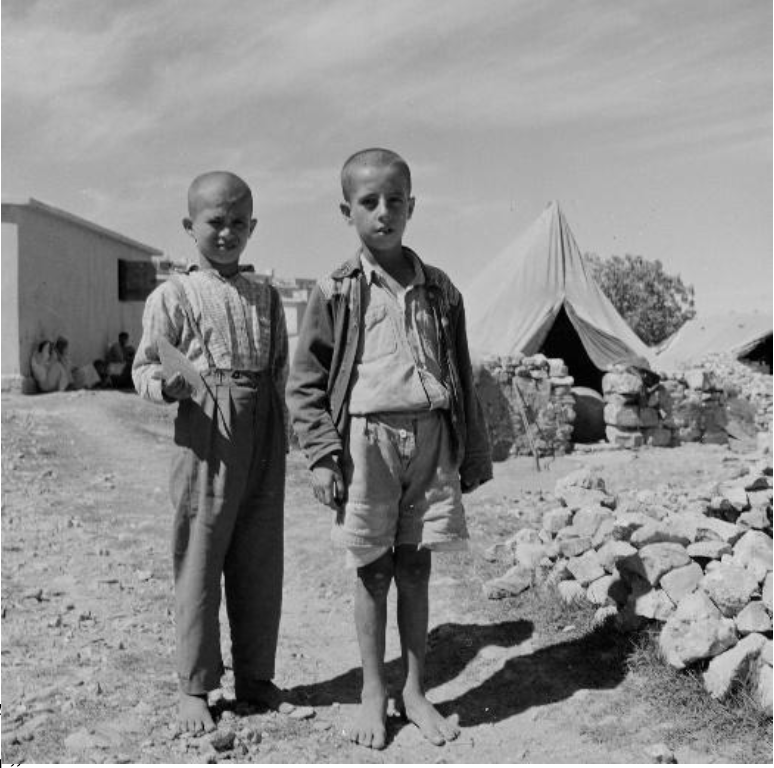

Iconography was instrumental in effectively communicating Dar al-Fata’s core-message of Palestinian identity and rootedness. An unsentimental acknowledgement of exile informed Ellabbad’s works. Indeed, he hoped to create a true portrayal of his displaced readers (fig. 9) and their heritage. In The Palestinian Alphabet (fig. 2), examples of national costume — a keffiyeh and a Bethlehem dress — are portrayed. Referencing Yasser Arafat’s iconic black and white keffiyeh, the poster makes a clear association between tradition and resistance. Similarly, the cactus (fig. 2) symbolizes patience in the face of hardship. Surrounded by freedom fighters and hand grenades, Ellabbad’s cactus references the work of Palestinian artist Zulfa al-Sa’di, who exhibited a cactus still-life alongside portraits of colonial resistance at the Palestine Pavillion during the 1933 First National Arab Fair. Olives signified the persistence of Palestinians and their connection to the land — ‘‘we are staying…forever.’’ The Jaffa orange, shown in Al-Bayt and Jerusalem is in the Heart, alludes to the Nakba — the mass forced displacement of Palestinian peoples after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. Immortalized in Ghassan Kanafani’s Land of Sad Oranges (1962), the appropriation of Palestinian orange plantations encapsulated the loss of the nation. By drawing from and contributing to images of traditional clothing, plants, and fruit, these posters directed children towards nationalism and resistance as a source of common identity and self. As Rosemary Saigh details in her 1979 oral history, these narratives helped counter feelings of estrangement and exclusion among displaced Palestinian youths in Lebanon, instead incorporating them into the ‘vanguard’ of an international anti-imperialist struggle. Ellabad’s Alphabet thus not only teaches the rudiments of Arabic writing, but the building-blocks of Palestinian identity, and what that kind of radical identification could mean in the wider milieu of global politics.

Figure 8. Tile 9 of Al-Bayt (Home) poster.

Figure 9. NRWA handout photo from the Israeli-occupied Westbank, undated.

The purpose of this paper was to contextualize and discuss the origin, form, and nature of three Dar al-Fata posters, in order to assess the significance of the organization and its output. This is, of course, difficult to quantify. Over 4 million books and posters were distributed in numerous different languages during the company’s existence. This already impressive number is accentuated by the fact that Dar al-Fata al-Arabi operated in a practically empty market. Moreover, as illustrated in this essay, the aims, artistic movements, and ideas that surrounded the PLO formed the potent and inimitable nucleus of all its works.

It is the latency of their propaganda that makes these three posters so intriguing. They are not the superficial instruments of grown-up politics converted into pseudo-pedagogical forms but are instead genuine in their aims and messages. Whilst not acknowledging themselves as political propaganda, they nevertheless incorporated the major motifs and beliefs of the mainstream form. Each work approaches its views moralistically and articulates them as one might in a fable, speaking to the questions of injustice, identity, and belonging that loomed over the lives of its audience.

About the Author

Charlie McEvoy is a student in the dual BA program between Trinity College Dublin and Columbia University.

Bibliography

(Full text with notes can be viewed here)

“Zakaria Tamer: The Master of (Children’s) Stories.” The Middle East Revised, April 10, 2014. https://middleeastrevised.com/2014/10/04/zakaria-tamer-the-master-of-childrens-stories/.

Abufarha, Nasser. “Land of Symbols: Cactus, Poppies, Oranges and Olive Trees in Palestine.” Identities 15, no. 3 (May 30, 2008): 343–68.

Alqudsi, Taghreed Mohammad. “The History of Published Arabic Children’s Literature as Reflected in the Collections of Three Publishers in Egypt, 1912-1986.” PhD diss., 1988.

Al-Sarai. Nahj Al-Faradis. Miniature, 1465c. (The David Collection) https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/materials/miniatures/art/15-2012.

Ellabad, Mohieddin, and Zakariyya Tamir. ‘‘Al Bayt.’’ The Palestine Poster Project Archives. https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/al-bayt.

Eltouni, Helmi. “Jerusalem Is in the Heart.” The Palestine Poster Project Archives, August 18, 2015. https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/jerusalem-is-in-the-heart-3/.

Farrell, Stephen. “Side by Side, Glimpses of Palestinian Refugee Camps Then and Now.” Reuters, December 12, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-israel-palestinians-unrwa-refugees-wi-idUSKBN1YG1FI.

Firdawsi. Shahnama. Miniature, 1600c. (The David Collection) https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/materials/miniatures/art/48-1973.

George, Alan. “‘Making the Desert Bloom’ a Myth Examined.” Journal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 2 (1979): 88–100.

Issa, Perla. ‘’Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon.’’ Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. ’https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/6590/palestinian-refugees-lebanon.

Khan, Hassen. “Revolution for Kids: Dar El Fata, Recollected.” Bidoun: Noise 19, (2010). https://bidoun.org/issues/19-noise#revolution-for-kids.

Khoury, Nuha N. “Where Are You From? Writing Home in Palestinian Children’s Literature.” Third Text 24, no. 6 (2010): 697–718.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut’s Global Sixties (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Maasri, Zeina. Off the Wall Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War. London: I.B. Tauris, 2009.

Renfro, Evan. “Stitched Together, Torn Apart: The Keffiyeh as Cultural Guide.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 21, no. 6 (2017): 571–86.

Sayigh, Rosemary. The Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries. London: Zed Books, 1979.

Shabout, Anneka Lenssen, et al. “Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents - Visitors’ Impressions of the 1933 Palestine Pavilion at the First National Arab Fair,” Post MOMA, April 11, 2018. https://post.moma.org/modern-art-in-the-arab-world-primary-documents-visitors-impressions-of-the-1933-palestine-pavilion-at-the-first-national-arab-fair/.